“Race has always been something that I'm very aware of…”

I met Bryan on a Zoom call with Friends from all over the US. It was obvious that he had read a wide range of early Friends literature and was knowledgeable and thoughtful about Quaker faith and practice. He told me later, “I like reading the writings of the early Quakers. I'm very interested. I like some aspects of Quakerism, for sure, and find them very inspiring, but I am a devout Orthodox Christian.”

He has asked that we not use his last name. Given how heated the topic of immigration is in the US now, I thought it was a good idea.

Here’s part one of my interview with him, lightly edited for clarity and length.

Judy Maurer

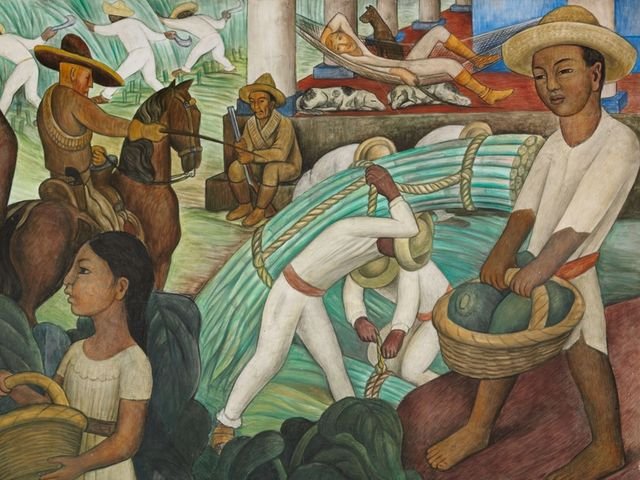

Mural by Diego Rivera

Would you like to start by talking about your family?

Bryan

My mother was from Mexico. I'm half Mexican, and grew up speaking both Spanish and English at home. So I have two first languages, although as we got older, my siblings and I would reply to her in English. I can understand Spanish, but it takes a little more effort to speak it. It's almost like there's two different parts of the brain. One, how we use our voice to speak it, and then the other part to hear it and then understand what we're hearing.

But it’s just a practice thing. Probably the most important thing in learning a language is the speaking. I can feel a little embarrassed or shy about it, but that's definitely the part that's really going to propel you forward.

Judy Maurer

That's true. I learned Spanish as a teenager. Your mother is Mixteca? Do I remember that correctly?

Bryan

Most Mexicans are considered mestizo. I had only recently learned that my DNA comes from the Mixtec people in Mexico, and that's only because I took two different DNA tests from two different companies, and one of them started including Native American groups. So that would include the Mexican American Native groups as well as South, Central, and North American groups. I thought that was interesting, because my mother never spoke about that. In fact, I don't think that she really even knew how much Indigenous blood she had. She never took a DNA test. She passed away before she did that, but my brother and I have done it. My father has done it, and several of my cousins and aunts on my mother's side have, too. She probably had around 50 percent Indigenous Mexican DNA, because I have about a quarter.

Note: Mestizo is a widely used term, but some view it as problematic because it originated in the Spanish colonial system of castas. Colonial Spaniards had specific terms and sets of privileges (or none) to go with each term. Mestizo meant 50 percent White, 50 percent Indigenous. Because Bryan and I are talking about the legacy of settler colonialism in Latin America, I feel this is an appropriate use of the term mestizo. Also, Bryan used the term to describe his own mother. Who am I to object?

Judy Maurer

That's the Mexican experience, right?

Bryan

Yes. In fact, the data shows that the average Mexican has about 30 to 40 percent Indigenous DNA, which is quite a bit.

I remember my mother talking about growing up in Mexico. In the class system there, the Indigenous population is at the bottom of the stack, especially the ones that speak their language and dress in more traditional dress. The average person in Mexico, who also is darker-skinned than the average European-American, to an outsider looks pretty much the same. Yet, there's a big class difference there. Also the lighter the person — the more European they are — the higher in that class system they will probably be.

But there's a term they use in Mexico to call people with lighter hair, lighter skin, lighter eyes. They call them guero. It can also be used as a pejorative. So even though you might be socially higher, they can view you as not as good as them in some ways.

Judy Maurer

That's right. That was totally my experience in the US Southwest where I grew up. It’s like we copied and pasted it in.

Bryan

Interesting. Race has always been something that I'm very aware of in my life, because of growing up in a mixed-race family. My mother and quite a few of her sisters came to the United States to go to universities. This is where they got married and lived their lives. They all have Mexican accents and are darker skinned than the average American. People would see them and think “that person is Hispanic,” although they were a little bit lighter than the average Mexican. Because of their accents and how they looked, I would notice how people would treat them.

Sugar Cane by Diego Rivera

I have light enough skin that I present as White. I didn't receive the same type of treatment they did. I knew that they were being treated differently. Sometimes it would hurt me as a child, growing up seeing how my mother was treated right in front of me in public.

It was coming from people who would probably not consider themselves racist at all. They may not even realize that they're treating someone that looks different than them and may have an accent. I would see these types of things over and over again. Sometimes it was being outwardly racist and mean — mostly not. But still, there was something there and then hearing people that I would work with, or people that I associate with in school or whatever, all of whom would not consider themselves racist. But in the way they speak, there's underlying racism there.

Judy Maurer

Exactly. Do you have any examples of that?

Bryan

A lot of what I deal with now is cloaked in joking. They might say something in a little racial undertone in a joking way. If they know what my heritage is, they might turn to me and say, oh, you're probably more Spanish anyway, which obviously wasn't true. I am about just as much Spaniard as Indigenous. I just happen to be lighter-skinned because my father is Swedish.

People will say little jokey type things that are racially insensitive, that they don't really see as being racist, because they said this little joke.

Judy Maurer

Why do they say that? Do you have any idea?

Bryan

I don't know. Maybe they think it's funny and in a group of all light-skinned people, it just kind of comes out, and they all giggle about it.

Judy Maurer

And does it ever happen that one of the light-skinned people say, hey, that's not really funny.

Bryan

I've never heard them say anything like that. If anybody says anything, I say something. I can sometimes be witty, so if I can think of something quick enough, I'll throw a kind of boomerang right back at them. Not in a cruel way, but it's my way of saying that wasn't funny, that was racist.

Because when someone does not consider themselves racist, I don't think that they would consider the racially insensitive joke that they told to be racist. I don't even think they would consider it racially insensitive. They would just say, it's just a joke.

Judy Maurer

I hate that. It's just a joke. I worked in domestic violence prevention for a few years. Some of the abusive men would say something horrible and say, Oh, it's just a joke. Can't you take a joke?

Bryan

Right? I mean, that's just a way of glossing over what they did. If they know that it was wrong or cruel, so they try to sweep it away with saying it's just a joke.

Recently, I had a conversation with a friend at work. She's politically conservative in some ways. I don't remember the full details of this conversation, but she was making comments about speaking English in America, because it is “our” language. She was referring to someone who was in a situation here in Utah where we live. So I said, “It’s interesting that you say that, because this used to be Mexico. The border went all the way up to Oregon and incorporated Utah, California, Arizona, and New Mexico. Spanish was the official language here first, not to mention all the different Indigenous languages that are even still here, that were here long before that.

Note: The Mexican-American War ended in 1848, with Mexico losing one-third of its territory to the US — what is now Utah, California, New Mexico, and most of Arizona.

She didn’t really respond. I was being nice when I said that, because I would rather have conversations with people even though it might trigger an emotional response within me, because I think that more good can come out of a deeper conversation than if I was to react out of some emotion.

She told me a news story about some soccer team — a younger teenager group. I don't quite remember. They were playing against another team in a match, and then the referee stopped the game because one team had decided to forfeit. It turned out that the coach of the other team kept speaking to the kids in Spanish. The team and coach could all speak Spanish and English, but the coach was communicating with them in Spanish, and the referee and the other coach and the other parents didn't like that. They said they didn't know if the coach was telling them to cheat or to kick the other players or something. They had no way of knowing. They didn’t like that and they put a stop to the game.

So we discussed that a little bit, and in a nice way, I pointed out that it just comes from fear. What makes them think that the other coaches would be saying something like that — to cheat — just because they couldn't understand them? If they were speaking English and the parents couldn't quite hear what was being said, they wouldn't have suspected that the coach was encouraging them to cheat. And so I said, “it just comes from a place of fear. Also, what does that say about how you feel about yourself, or how the parents felt about themselves, that they would jump to those conclusions?”

I stopped the conversation there, because my emotion was starting to get up to a point where I couldn't keep it in check. So I went back to work. Maybe an hour or so later she came back to me and she said, I was really thinking about what you said and you were right. I realize there's nothing to worry about. There would be really no difference between whether they were speaking a different language and I couldn't understand what they were saying, or that I just couldn't hear what they were saying.

But that was the last time she has ever mentioned anything like that in front of me. So I don't know if she had changed her perspective or if she just decided not to have those types of conversations with me.

Judy Maurer

But the fact that she came back is good. I had a painful conversation with a coworker who was complaining about the same thing — Hispanic men at the grocery store speaking Spanish to each other. She said, they're always talking about me. And I said, I understand them. They're talking about the last soccer game and all sorts of things.

Bryan

Maybe it comes with a sense of pride that they're so special that they might be the focus of the conversation of someone that they don't even know.

Judy Maurer

Oh yes, she clearly thought that I just wasn't attractive enough for Hispanic men to have been talking about me! [I laugh…]

Bryan

Yeah, that reminds me of growing up as well. Some of my close friends liked to go to this little diner and would have something to eat and some coffee. Here in Utah, Mormons don't drink coffee, and so it took quite a while for coffee shops to kind of catch up here.

So we'd go to this little cafe, and sometimes there would be someone speaking Spanish within earshot, and it was always the same friend who was worried about what they were saying. He would ask me, “Bryan, what are they saying? What are they talking about?” So I’d translate a little bit of their conversation, and it never had anything to do with us. They were just talking about their own lives. And he would always say, “I just want to know if they were talking about me.” And I'm like, “Why would they be talking about you? They don't even know you.”

It seems like it comes down to really being self-conscious, and because someone is speaking a different language, that self-consciousness starts flaring up and then turns into fear or something.

It also reminds me of, I don't know if this was staged or not, but there was a little video clip I saw quite some time ago of someone standing in a line at a grocery store, and they were having a conversation on their cell phone in a non-English language. The person in front of them kept turning around and looking at them as if they were bothered by the conversation. Finally, the person turns around and says, “Why don't you go back to your own country if you're not going to speak English?” And the person says, “I was speaking Navajo. This is where I'm from.” That was just really interesting to me. I don't know if that was a setup or what.

Judy Maurer

I could imagine that happening.

Bryan

Yes.

Judy Maurer

Navajo is such a different language. It’s from the same language family as Tlingit in Alaska, which I find fascinating. Your mother never talked about her Indigenous background?

Bryan

I just think that she didn't really know. That's also something that I've noticed with Mexicans, because the Spaniards did a really good job of washing out their culture. The people there who are about 30 to 40 percent Indigenous don't even know what tribe or what culture they come from. They know nothing of it. They may not even really put it together.

The reason why we look the way we look in Mexico is because of the Indigenous people mixing with the Spaniards, but not just Spaniards. Mexico is a very, very big melting pot. There were people from North Africa who came in with the Spaniards, and people from all over — Jewish people, European people, African people. It’s a small percentage, but it's larger than you would think, of Jewish DNA in Mexico as well.

Judy Maurer

I noticed that in Cuba too. There were people with German last names and English last names who had been there for generations.

I worked on the census in 2020 in Portland. By the end they were sending me to Spanish-speaking households. There was a question on it about your racial identity. Hispanics, especially recent immigrants, would answer it very differently from Americans. There was a list of things you could choose from. Except for one person, all of them said, I’m Mexican. Or Guatemalan — or whatever country they were born in. Then they would point to a child and say, “little Josecito here, he's American. He was born here.”

They did not choose Indigenous, even though I could clearly see they were Indigenous, or at least partly. Only one chose to say he and his wife were Indigenous, and he didn't know what tribe or group he was from.

Bryan

That partially comes from the fact that they don't know, because the Spaniards really washed out all those cultures. Also, because of that class idea, they don't want to admit, even if they know, that they have some Indigenous blood. Another thing I've noticed is that you can have mom and dad and Abuelito and Abuelita, grandma and grandpa — they all immigrated from Mexico and are Mexicans. But their children who were born here, they call them Americans.

I've noticed that even with my cousins from Mexico who have immigrated here, they're like that with us, cousins that were born here. Also, Mexicans that I know who’ve immigrated here, even if I'm not related to them, don't tend to think of me as Mexican, even if we've had many discussions about my family and things like that. They'll look at me as having Mexican heritage, but not being Mexican.

So I think it's just a different way of thinking how we, in the US, think about heritage and race and things like that, especially when a culture might be considered a different race, and you don't look like the other race. There's so much that comes with that.

I've had this conversation with my cousins before, and how anytime there's something that you're filling out, and they start asking those race and ethnicity questions. I always hate doing that, because they're so confusing to me, because even though I'm light skinned, when people ask me, I say, “I'm Mexican.” That’s how I’ve grown up to identify. My mother was a stay-at-home mother for most of the time we were raised, speaking Spanish with us, and she had enough sisters living nearby; we had the big Mexican family type thing, and always getting together with everybody, on everybody's birthday.

So I always kind of thought of myself as Mexican. At least if I'm pressed to choose sides, that's the side I choose, because I just identify more with that. But it's also interesting that in the US, we kind of push people to choose.

In some of those questionnaires, they don't ask the right questions. They'll ask if you're Hispanic and then what race you are, but sometimes they don't allow you to choose Hispanic and White, but a person from any country or ethnicity that speaks Spanish or Portuguese can be Hispanic or Latino.

So it's just it was always confusing to me.

Note: “Latino” can be seen as a problematic word because it has a masculine ending. In Spanish, if there are 99 women in a group and one man, then the nouns and adjectives describing that group must be in masculine form. To solve that problem and to include non-binary people, some use the term “Latinx.” However, “Latinx” is not pronounceable in Spanish, and many people do not embrace the term. Bryan used the words Hispanic and Latino, and I follow his lead.

Judy Maurer

I remember being in a workshop here in the US and people were surprised that Hispanic wasn't a race.

Bryan

Well, even in Spain and Portugal, because of the Arab rule for hundreds of years, there's a big mixture of Arabs and Jews — whether they're European Jews or or Middle Eastern Jews. There’s North African, and then the groups that were there even before the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking groups.

Judy Maurer

Yes, I can pass easily for a northern Spaniard, but if I'm in southern Spain, I stick out in the crowd. I’m taller, lighter. The classic Spanish look is more Arab.

Bryan

That's definitely what people think of when they think of Spanish — olive skin, darker features.

Judy Maurer

You’ve thought about this a lot.

Bryan

I think just growing up, what I would say biracial, even though I'm very light skinned, so I pass as White, and I live in the United States, where there's more light-skinned people. Because of having family members who aren't, race is always in my face. I notice what people say and what people do. I think that people would really be shocked to hear that the vast majority of people who think of themselves as not racist might say and do things that are racially insensitive.

Judy Maurer

Yes, I bet. Including moi, unfortunately, too. Can you give examples of that, unless it’s too emotionally involved for you?

Bryan

I hear people being triggered by hearing someone speak a different language. And it seems to really be more triggering when it's a different race speaking a different language. Say someone heard someone speaking a different language, and they turned around and it was White people speaking Norwegian or Swedish. They probably wouldn't have the same reaction as if they turn around and it's someone speaking a Nigerian language or Spanish, and the person had dark skin because maybe they were from South America.

Judy Maurer

Yes, I think you’re right. Before the pandemic, I went to a Mennonite church that was mostly Latino. One of the things I loved about it was that there was very little distinction between the people who were Indigenous (mostly Mayan) and the people who were Spanish descent. Except for family members, they all used usted to each other. It made me a little uncomfortable, addressing people who I regarded as my “brothers and sisters in Christ” with the formal usted.

Bryan

I hear Mexicans and other Spanish people say usted a lot. In English, at least these days, we don't tend to use any formal language. In fact, when Quakers speak plain, that can sound like fancy language or very formal language.

Judy Maurer

That's right! When we use “thee” these days, it has a formal ring to it.

Bryan

I grew up using that language in prayer. I think that it came from the King James Version of the Bible, and then we used it in prayer. In English, back in the sixteenth century, you could say “you” and be speaking to a group, or to one high-status person. But to say “thee” or “thou,” you’re speaking to one person. So plain speech came about because Quakers refused to use the royal “we” speak. A high status person wanted to be addressed as “you,” so the plain speech would be like, “No, we're not playing that game.”

Now when I think about using thee and thou in prayer, what if you're a Trinitarian? Sometimes I'm like, does that fit or does it not fit? Should I say “you,” for plural?

Judy Maurer

That's a good point. I loved worshiping in Spanish where God was always tú, which I really liked.

Bryan

It's less formal.

Judy Maurer

Yes, and more intimate.

Bryan

It does seem more intimate.

Judy Maurer

Now, among Quakers, you can slip into “thee” to be more affectionate. It's an affectionate term, which I really like, although around here people don't quite use it as much as back East. I should say I grew up in a crazy little town in rural Arizona, but my parents were urban New Englanders, so I have somewhat of the dual culture bit going on in my family, too.

Bryan

Were you raised Quaker?

Judy Maurer

No, my father was an Episcopal priest. I got into Quakerism in college. It’s amazing how much you know about Quakers!

Is there anything more you want to say about the racial situation?

Bryan

Just that I know people who would probably die inside If they ever thought that they had done anything racially insensitive, but they do those things and don't even realize it.

It makes me be more watchful and more attentive about my own thoughts and my actions and my speech. I think that people can go too far in either policing each other or policing themselves.

I kind of analyze like, if I suddenly have a knee-jerk assumption about someone I don't even know. Why did I do that? I'll notice these things as they pop into my head. And then I instantly, pray a prayer, Lord, please forgive me for that. Please heal me from that. I do it because I mean it. I want to be forgiven for even just that thought. Christ said that if we lust in our hearts or in our minds, it’s just the same as committing adultery.

I would love to be able to love as God loves, and see as God sees. And so anything that is the opposite of that, I want to be healed from, so that I don't do the opposite of love anymore.

Judy Maurer

That is wonderful. A few weeks ago I was volunteering in a charity shop where the benefits go to their program for the houseless. Sometimes, houseless folks stick around in the charity shop. The other day I was talking to one of them for quite awhile. Then he smiled. He had no teeth, and immediately I reacted in my mind, because in America, you have to have good teeth, right? I hope my reaction didn’t show on my face.

That's a really good idea to pray about that.

End of Part I. Stay tuned for Part II in an upcoming issue.